[REPORT] Going to the gym with MLIR: Writing a recompiler for DEX instructions

2024-12-07

Prologue

Hi there, how has everybody been?

I hope everyone's having a great day, this article is about lifting and lowering DEX instructions in MLIR, utilizing the framework in analysing and optimizing the DEX format.

The blog is intended as a report submission for CS265 here. The report focuses more on the high level details. The project also discusses the ease (or uneasiness) of executing the project, meanwhile introducing the benefits of MLIR with its elements in the ecosystem

The report is about 3700 words, or 15 minutes of reading. The editing cut-off is 12PM PST Dec 17th 2024.

I also include a supporting section to recap different terminologies for unfamiliar readers.

Please try out this song while reading, it really soothes the mind. I hope everyone enjoys :)

Reader supporting section

Open Reader supporting section

This section introduces some terminology and/or acronyms that reviews from my friends deemed might be important context.

Terminology

-

SSA: Static Single Assignment, a form where each variable is assigned exactly once, enabling easier optimization and analysis. This form is enforced in MLIR. We'll see the useful feature of this in the translation section.

-

Phi (): A phi node is an SSA (Static Single Assignment) construct that selects a value based on the control flow predecessor, allowing variables to have multiple incoming definitions at a basic block merge point.

-

Block arguments: Equivalent to phi (?!) but in a different form.

-

Dialect: A custom language extension in MLIR like

arith(stands for arithmetic) orcf(stands for control flow) orfunc(for function related things) used to represent IRs. -

Operations: A term (and concrete thing in MLIR's C++ API) that can be used to represent different concepts in MLIR. This ranges from higher-level concepts like function definitions, function calls, buffer allocations, view or slices of buffers, and process creation, to lower-level concepts like target-independent arithmetic, target-specific instructions, configuration registers, and logic gates.

To give an example of the two terms, the dialect arith features different operations such addf (adding two floats) or addi (adding two integers) or cmpi (comparing two integers). Another example is the func's dialect's func (to represent a function) or return to represent a return call or call to represent invoking a function.

Acronyms

-

LLVM: used to mean Low level virtual machine, but now is an umbrella term for a collection of modular and reusable compiler and toolchain technologies. Another meaning for LLVM is the subproject LLVM within the LLVM collection. The subproject provides reusable components for code generation, optimization, and analysis, enabling developers to build high-performance, platform-agnostic tools.

-

MLIR: stands for Multi-Level Intermediate Representation. A flexible, extensible compiler infrastructure within the LLVM project designed to support multiple levels of abstraction and domain-specific optimizations. It provides a unified framework for building high-performance compilers and tools tailored to diverse hardware and programming models.

-

DEX: Stands for Dalvik Executable, which is a format used on Android before being replaced by ART, which stands for Android runtime.

-

MjolnIR: A custom IR for representing DEX instructions built from MLIR's facility. The library's current implementation uses this IR primarily.

-

Basic block (BB): a straight-line code sequence with no branches in except to the entry and no branches out except at the exit.

-

CFG: Control flow graph, the graphical representation of control flow or computation during the execution of programs or applications. On its most basic level, a CFG (control flow graph) contains a bunch of BBs (basic blocks), which are glued together by control flows

Introduction

The MLIR project from the LLVM framework provides a framework for building reusable and extensible compiler infrastructure, allowing for a unified handling of different IRs within the same framework.

In the case of the library Shuriken from Shuriken Group for Dalvik Executable (DEX) file analysis, we can leverage the MLIR by extending a somewhat 1-to-1 mapping of DEX to MLIR, the newly created IR (MjolnIR), allowing us to use the much more mature framework for analyzing the binary itself. As DEX is used as a mean for transportation from a server to an android device where it is compiled into ART for installation, being able to optimize the bytecode size of dex allows us to save cost on networking as well as server and android device's storage cost.

In the future, MjolnIR will be used in optimization, obfuscating, deobfuscating the Dalvik Machine Bytecode.

This project (and this blog post) wouldn't be possible without the guidance of Eduardo (Edu) Blázquez González (Fare9), (Eduardo), a PhD doctorate and a compiler engineer at Quarkslab in developing, lifting and lowering the IR. This summer, Edu's the one that reached out to me on twitter to befriend me :) We chatted about compilers and stuff, and later he introduced me to the codebase. He's been helping me with onboarding the codebase infrastructure, together with emotional support and chatting about life hahahah :)

I am also grateful to Max Willsey, the professor of the compiler graduate class CS265, for allowing me, an undergraduate, to enroll as well as guiding me in the direction of the project. Throughout the semester, there were some assignments where I fell behind. I know that opportunities are hard to come by and I really took every lesson to heart. I thank you for your advice and your bet for taking me into the class :)

Much work is needed in supporting the full instruction set of DEX as well as optimization of it. The project report will discuss the current work (which is a subset of the DEX instruction set) as well as future work.

Planning

Version control and contributions

All code for the project is under the Shuriken Analyzer repository, which is under the Shuriken Group's ownership.

The group also includes other projects, such as

- LLVM/MLIR dependency fetching tool: To power CI/CD for this project.

- Telegram bot for Shuriken : for issue filing and status request, as our group's communication is mainly via telegram.

My contributions for the project are shown separately via the issues and pull requests

Goals and current status

In analysing the DEX format, we need to parse the DEX file, construct a CFG (non-MLIR, and non-SSA), and then translate the CFG to MLIR's SSA CFG, apply some analysis, then translate it to smali, and then translate smali to dex (via 3rd party tool).

Smali is the human-readable assembly format for the dalvik virtual machine. Edu's provided us with a good write-up for smali that I think necessitates a read. Here, I show a small "Hello World" program written in smali that is compiled from java.

# This is a comment

.method public static main([Ljava/lang/String;)V

.registers 2 # We use a total of 2 registers here.

# Get the PrintStream object into register v0

sget-object v0, Ljava/lang/System;->out:Ljava/lang/PrintStream;

# Get the const string "Hello World" into v1

const-string v1, "Hello World"

# Invoke v0's println method on v1

invoke-virtual {v0, v1}, Ljava/lang/PrintStream;->println(Ljava/lang/String;)V

# return void

return-void

.end methodThe reasoning for this is that smali is an easier output to work with than dex. In dex format, we need to maintain different tables of strings, types, methods and classes in the pre-header before we get to output the actual DEX. To make matters worse, control flow is done via offsets, which disrupts optimization and requires recalculation of offsets.

In smali, all is resolved via text references instead. In such a short amount of time (~ 6 weeks), it's hard to achieve true circular transformation (DEX->MLIR->DEX). I therefore opted for (DEX->MLIR->smali->DEX) first (actually at the time of writing this (Dec 7th 2024), I'm even nervous to see if we can get DEX->MLIR->smali for submission).

With the naming of the MLIR's dialect being MjolnIR, the goal of the project is divided into two fronts:

- Achieve the circular transformation of: DEX -> MjolnIR (MLIR) -> Smali.

- Survey some analysis/optimization provided by MLIR, using our new IR.

In parsing the dex and constructing the CFG, the job was done by Edu prior to me joining the team. There was also an effort in lifting some subset of DEX to MLIR in the KUNAI repo by Edu (recorded here).

Therefore, my responsibilities in the project are to set up MLIR, port over and maintain the lifting process of DEX, figure out the optimization and lowering aspect.

The diagram shown below details the steps we need to take in the project.

MLIR's operations and values

Operations

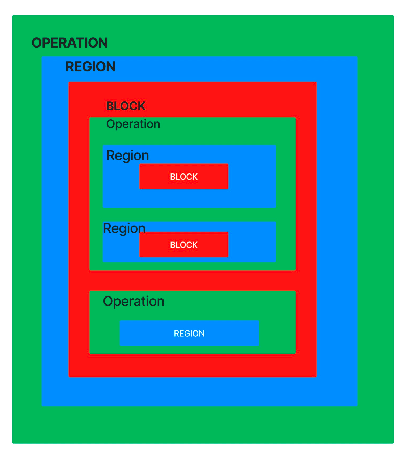

MLIR is built from what are known as "Operations," which are used to describe many different levels of abstractions and computations.

Every operation has a unique name, often written in the format dialect.operation_name. For example:

- arith.addi (integer addition in the arith dialect)

- func.func (function definition in the func dialect)

An operation may contain one or more regions, which in turn contain blocks of other operations. This allows hierarchical nesting, making MLIR very expressive.

On the top level, the MLIR features a ModuleOp, which is a container operation of a single graph region.

In lifting DEX to MLIR, we think of

- An input DEX file comprises 1 up to 65535

ModuleOp, where eachModuleOprepresents a class. - Each method (class's function) in the DEX file is a

MethodOp, a MjolnIR dialect's operation similarly to thefuncoperation in func dialect. - Each method might have control flows, which glues together basic blocks.

Although a simple 1–1 representation, MLIR can feature much more complex hierarchy, as demonstrated below. We, however, rely on the rigid structure we've defined for ourselves to simplify the lifting and lowering processes.

The following diagram showcases MLIR's recursively fluid structure.

Values

An important thing to notice is how the SSA form is represented in MLIR, which is done with mlir::Value. The MLIR Value plays an important role in the project; operations take in values and produce values, passing them to functions and blocks (these are operations as described above) to get out

some value or to establish control flow. Hence, frequent trips to mlir::Value's doxygen are needed. A fun thing to note is that with mlir::DenseMap, mlir::Value can be hashed; this powers both the lifting process and the lowering process.

To glue together the concept of operations and values, let's look at an example. Given an operation such as the integer addition

mlir::arith::AddIOp, MLIR gives us different accessors such as getLhs(), getRhs(), getResult() to access its values.

Each of these values can consequently invoke getParentBlock() or replaceAllUsesWith() to further manipulate themselves.

In a big picture with operations introduced above, the MLIR Language Reference succinctly says:

MLIR is fundamentally based on a graph-like data structure of nodes, called Operations, and edges, called Values.

Dissecting MLIR

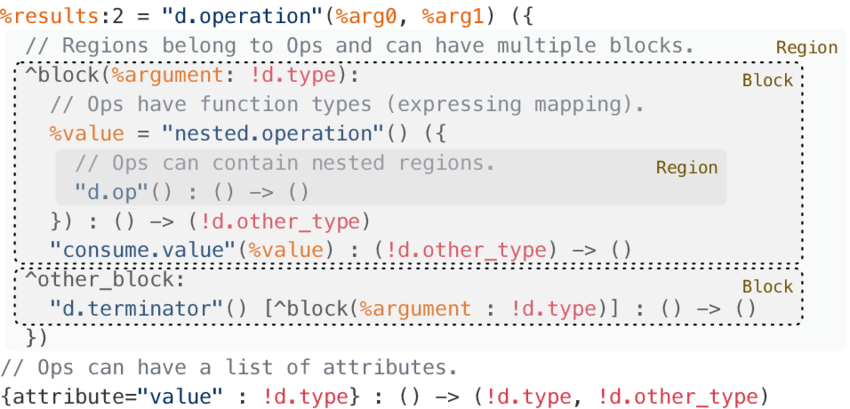

Knowing how MLIR's operation and value works plays a crucial role in getting the recompiler working, as lifting, optimizing, and lowering all depend on them. I think therefore, it's also important to look at its textual form.

A pretty full (for our sakes) view of MLIR is shown below:

Below, I show some demos of some textual MLIR.

From Jeremy Kun's tutorial (a pretty cool person and maybe my idol), which the report author heavily relies on:

// The first `func` is the dialect's name. The second `func` is the operation's name

func.func @main(%arg0: i32) -> i32 { // Variable names (SSA values) are prefixed with %

// by convention naming of %arg0 means it is a different subclass than %0

%0 = math.ctlz %arg0 : i32 // Here we're using ctlz operation from math dialect

func.return %0 : i32 // return op from func dialect

// taking in the ssa value %0 of type i32

}A special thing for dialects in MLIR is that without a compiler writer's specified instruction to print an IR in textual form, MLIR will faithfully print everything that an operation has to the terminal (auto-generative aspect). This helps me quickly debug implementation issues in the project.

Parsing, cmdline and cmake

Supposedly, the project will provide a command line tool for user to input in either a path to a DEX file or a folder of DEX files so that the tool can either lift and lower the DEX file(s).

The command line executable is handwritten with the formatting via fmt.

Below shows the interface of the entry point executable when ran with --help:

./shuriken-opt --help

USAGE: shuriken-opt [-h | --help] [-d | --diagnostics] [-f|--file file_name --lift -g|--graph --lower --opt]

-h | --help: Shows the help menu, like what you're seeing right now

-d | --diagnostics: Enables diagnostics for shuriken-opt

-f | --file: Analyzes a file with file name, needs additional information

-lift : Lift the dex format up to MjolnIR

-lower: Lower the lifted MjolnIR down to smali (Enables lift when this is opted)

-opt: Run some default optimization (Nop removal for now)

-g | --graph: Dump the graph in dot format (needs a file)To maintain the build of the project, I opt for CMake, which is both Shuriken's build system and LLVM and MLIR's build system. It's also a build system tool I'm most familiar with in the C++ ecosystem.

Dialect reusability and extensibility

A high selling point of MLIR is the ability to reuse its dialects and the ease of defining new dialects in it. This is no different for our library, with our dialect MjolnIR.

In MLIR, there are multiple ways to define a dialect. You can either opt for MLIR's C++ API way to define it. Even though quick, the downsides of this quickly catch up: tons of boilerplate and scattering codes scatter across different files, which screams "update me" whenever LLVM goes to a new version, introducing breaking changes.

Another way to go is via TableGen, a generic language to maintain records of DSLs in a concise way. Benefits (that are relevant to the project) include:

- Centralized source of truth: Every aspect of an operation should be in the same localized place. This is true to some extent. Some parts of TableGen syntax regarding MLIR are still a bit hazy to me and require digging through either the MLIR docs or the source code itself for clarification; I think this is expected for any beginners.

- Boilerplate removal and auto generation: defining and extending a dialect in TableGen syntax is easier than in C++, due to its cutting down on non-needed aspects when extending and its auto-generative nature.

Chapter 2 in the toy tutorial demonstrates this the clearest, I recommend a quick skim for confidence.

Introductory asides, it's clear we opt for the TableGen method instead. I'm also in favor of using TableGen since this is an opportunity to learn about new stuff!

In our library, we reuse two of the built-in dialects: arith, cf. We also extend upon this by creating new operations:

- A pseudo branch operation

MjolnIR.fallthroughsince entering a block in MLIR requires control flow but in smali the normalcy is to execute the next line after a branch if the condition is not met. - Two operations

MjolnIR.methodandMjolnIR.returnto replacefunc.funcandfunc.returnsince we need to capture extra infos about our method such as accessors such as public, private, static, etc... Thefunc.returnis obsolete since it requires that its parent isfunc.func, thus the need forMjolnIR.return.

Conclude

Doing the project in MLIR's system introduces several benefits:

- Reusing different built-in dialects from MLIR saves myself a lot of time from implementation design and implementation bugs.

- Everything in MLIR (for a beginner) fits well together. For example, the

cf.condbrandcf.brplays really nice with MLIR's SSA block arguments style, providing iterators to their respective block arguments. Having implemented the alternative phi node version in bril IR makes me realize how clean MLIR's SSA form actually is. In addition,mlir::Valueprovides different ways to identify if a value is from a function or block's argument or a normal value, this makes generating values for smali'sp{}(method parameters) andv{}(local variables) relatively easy.

Non-MLIR, NON-SSA CFG to MLIR-SSA CFG

From this point forward, referring to non-ssa CFG means that it is non-mlir and vice versa (as MLIR requires the SSA form in its CFG).

A special characteristic of DEX is that it utilizes (almost infinite) virtual registers without caring for stack space. This allows for a seamless construction of the program's CFG from the DEX format.

After constructing the CFG's non-SSA form, we translate it to MLIR's SSA CFG via Braun's SSA algorithm

On the high level overview, we keep an mlir::DenseMap between the original CFG's basic blocks to a BasicBlockDef, this is meant to replace the paper's currentDef[variable][Block].

struct BasicBlockDef { // stripped down version of BasicBlockDef

mlir::DenseMap<std::uint32_t, mlir::Value> Defs;

// ...

unsigned Filled : 1;

};In the BasicBlockDef wraps another mlir::DenseMap of uint32 to mlir::Value, this is how we're accessing the variable in currentDef[variable][Block] from the paper's algorithm.

When the original CFG's instructions ask to either read or write to DEX's virtual registers, we either get the value from our map between integers and mlir::Value in the current block, or we recursively call the query on the block's predecessor(s).

The query of a variable's definition in a block's map in the project is the equivalent of C++ MLIR's

mlir::DenseMap[mlir::Block*][mlir::DenseMap[std::uint32_t][mlir::Value]]Optimization and Analysis

In writing an optimization pass, MLIR offers a variety of tools for the job. Different machinery includes DataFlowAnalysis, Pattern Rewriters, generic operation pass.

In writing up this part of the project, the biggest obstacle is surprisingly not about learning the apis of different optimization tools, but actually verifying MLIR's and ourselves' dialect.

For time management, I'm opting for a simple pattern rewriter to remove all nops: the mlir::applyPatternsAndFoldGreedily pass. Using the pass runs MLIR's verifier on its built-in dialect, triggering a lot of errors on our compiler build. Despite this, fixing this was somewhat straight forward with MLIR's error messages (?!) and documentation on its operations.

Translation

Parameter versus local registers

The Smali IR differentiates between a parameter and a local variable with the prefix p or v. This in turn requires us to also somehow identify this in MLIR.

Fortunately with MLIR's helpful methods such as llvm::dyn_cast<>(), llvm::isa<>(), mlir::BlockArgument::getOwner() and mlir::Block::isEntryBlock(), it was relatively straightforward to resolve this, which will be shown in the next section.

Getting out of SSA

SSA value to virtual registers

Since SSA variables are only assigned once, we can assign each SSA variable to its virtual register counter-part by keeping a counter, seeing a new SSA variable means incrementing the counter and assign that SSA variable that newly incremented counter value.

We'll use C++ templating to do this with a class called SmaliCounter, generic on type Aspect.

template<class Aspect> // a template so we can reuse it

class SmaliCounter {

size_t counter = 0;

mlir::DenseMap<Aspect, size_t> counter_map;

public:

SmaliCounter(size_t start_from) : counter(start_from) {}

size_t get_counter(Aspect a) {

if (this->counter_map.find(a) == this->counter_map.end())

this->counter_map[a] = counter++;

return this->counter_map[a];

}

};We have 3 counters to keep track of: the parameters, the local variables and the basic blocks themselves. Let's respectively call them prc, vrc and bc. To determine a location to jump to, we input a mlir::Block* to bc and get out either a preexisting location or a new one, as indicated by get_counter.

The situation is a bit trickier with prc (method parameters) and vrc (local variables) since they're both mlir::Value. However, an interesting thing to note is that the method parameters are actually mlir::BlockArgument, a subclass of mlir::Value. This subclass exposes a method called getOwner that returns a block*, and the block in turns exposes a method to check if it is the entry block of a method or not.

Thus, if an mlir::Value is actually of mlir::BlockArgument and if it belongs to the entry block of a method, then it is a parameter, and will be inputted to prc and vice versa. I add the second requirement since a block argument can also come from different blocks that are glued together by control flow instead.

Dealing with phis (block arguments) (SSA destruction)

In translating from MjolnIR to smali, I opted for a simple out-of-ssa transformation introduced in class, slightly tweaked to fit MLIR's ssa block arguments fashion:

For every control flow (cf.condbr and cf.br):

- Copies the current arguments being passed into the true block,

to the actual parameters, which looks like (move* vA, vB)

- Inserts an instruction that jumps to the true block

if the operand to the instruction is true, which looks like (if-* vX, :block_Y)

- Copies the current arguments being passed into the false block,

to the actual parameters, which looks like (move* vA, vB)

- Inserts an instruction that jumps to the false block,

which looks like (goto :block_Y)

The cf.br case simply reduces down to the last two step.The following drawing executes the algorithm on a handwritten example.

Control flow combination

A quirky thing between MLIR and smali is how they differ in their branching.

In MLIR, we first obtain a boolean value from something like arith.cmpi. Then we use this value to feed it

into cf.condbr to either jump to a block or continue as normal.

In contrast, smali employs different kind of if-* instructions as a way to combine the MLIR's two-step approach.

For example, an if-ne is used to represent a arith.cmpi instruction of two mlir::Value, and then depending on if they're equal or not, jump to a block.

I'll once again use the SSA property to resolve this issue.

Upon a branching based on a predicate (cf.condbr), we can query the defining op of an mlir::Value to obtain its boolean defining operation (defOp) (step 1 in mlir). Notice that when we first encounter that defOp, we still generate its smali equivalent (since we don't know if it might be used once or multiple times or will be passed in to some other blocks). Then, we proceed to pick the correct branching smali instruction. Since the nature of SSA is a value can only be defined once, a single value cannot correspond to different defOps.

For the case that mlir::Value::getDefiningOp() returning nullptr, this means that it's a block argument. We just generate if-nez from smali.

For this part (translating), I think what troubles me the most is the fact that, to the best of our knowledge, no project exists to translate from a custom IR to smali. Combined with limited knowledge of both smali and MLIR, the cycle continues itself since not knowing smali well requires me to perform multiple iterations on the custom IR, which suffers again from limited knowledge of MLIR.

So what's going on right now, Jaz? What's next?

The project's progressing at a steady rate right now, with me and Edu's contributing on the MLIR side.

Contentedly, with different priorities both in my life (looking at you "full time recruiting") and in UC Berkeley (looking at you EE16B and EE126), a short timeline of 6 weeks renders the initial goals of the project somewhat incomplete. That is, although lifting and simple analysis of DEX via MLIR is achieved, some work is needed in translating MjolnIR to smali.

In retrospect, I think I should have thought ahead and started the project 4 weeks earlier (1 month into class). More familiarity with the SSA form, SSA construction earlier in the process would have expedited porting the lifter as well as writing up the out-of-ssa translation.

After the semester ends, I'll continue working on the MjolnIR-to-smali translation, besides supporting new DEX feature into MjolnIR and refactoring existing code. Then, some form of dataflow analysis on the new IR is expected.

With this new-found knowledge of MLIR, the next steps would be trying to write an ML compiler by extending upon MLIR's toy tutorial

But why contentedly?

I've been wanting to dive deeper into MLIR for a long time. When it was time to choose a project, in the back of my mind, I've had some doubts. But ughh, I want to learn, and I don't care if a project I chose ran into time constraints. It was important for me to learn about an industry's tools as well as put my mind to implement different algorithms I've learned in classes in the ecosystem.

I think VSauce's supertask's 17:42 to 20:07 captures the best the mentality on the project.

I hope everyone's enjoyed the little 15-minute read, I'll see everyone soon with some new blog post :)

Resources

Below lies the related resources I've visited during the timeline of the project.

Figures

Jasmine

Edu

Max Willsey

Jeremy Kun

Tutorials and Docs

A good tutorial read is MLIR's official toy tutorial. It helps me familiarize myself with the commandline, different elements in MLIR and different ways to do things, as well as their trade-offs.

Jeremy's MLIR tutorials brings a fresh change into LLVM's terse style of tutorial, I frequent the sites a lot and recommend if you're trying to learn more about mlir.

MLIR's doxygen page is much needed for resolving dependency issues as well as correct usage of MLIR's elements. I recommend familiarizing yourself with different operations' and values' method signatures.

MLIR's LangRef provides a good worldview about its ecosystem for a beginner.

ChatGPT and Claude are also (not really, but kinda) helpful tools in super boosting your learning about MLIR and LLVM's api.

Algorithms

Max Willsey's lesson about SSA form is much needed for the project. I also recommended another introductory perspective into the matter with Engineering a Compiler's chapter 9.3.

A read for Braun's algorithm is also required. Edu also posted about it for MLIR here, which forms the foundation for his implementation in KUNAI.