Building BRT.nvim - an atuin clone for my neovim workflow

2025-10-23

Introduction

Hello everyone, it's been a while since my last blog that's focused on developer tooling itself. In this post, I want to talk about a neovim plugin that I've made that has significantly improved my workflow productivity: BRT.nvim :)

As always, here's this blog's music recommendation: Bay trong chiều mưa by Nah

atuin and BRT.nvim

For adddd context, atuin is an ultra convenient shell history manager that when you press the uparrow, it provides you

with a fuzzy finder and allows you to press <tab> to accept a search result and <Enter> to run a command.

BRT stands for Build-Run-Test and the plugin's description on GitHub is "Build, run, and test your projects with 3 keystrokes." The motivation for building this is that when programming, I'm invoking the build, run and test commands quite often; I often alternate between the file in neovim that I'm coding and the terminal for invoking the commands and reading command stdout and stderr, leading to quite inefficient processes.

The vision I have for BRT is that I would want to shorten the development cycle: "run the usual command as effortless as possible" and to reduce the mental cognitive load from switching between the development file I'm in and the terminal.

Over time, I've also identified that when the command spits out an error including the location of a file, it would take me some brain cells to find the line indicating the file, and then I also have to remember which line number the error is on, and then I have to copy the faulty file name to my clipboard, and then go back to neovim to find and open the file and then jump to the line number to see what the code on that line is, and then go back to the terminal to read the error message for that line. Wewww, even reading all this makes my head a bit dizzy and almost cause me a stroke. Now, imagine if the output has 4 or 5 such error locations, you can start to see why it's getting really messy really fast.

The above deficiency is not something that atuin can solve; being able to rerun a command quickly doesn't mean much when the bottleneck is how you're locating the issue + debugging the problem as the command fails.

Throughout the blog, there are only pictures to showcase the behavior of the plugin. To actually observe how BRT works, you can check out this video which also shows the real time keystrokes when I'm invoking BRT.

For now, I hope this small text comparison would help you visualize the change in my workflow:

Before BRT.nvim:

Alt+Tab

→ find and run command in terminal

→ find error line

→ copy file name → back to nvim

→ Alt tab to terminal to read error message

→ Alt tab to neovim to start diagnosing

With BRT.nvim:

<space>b<Enter>

→ jump straight to error location for diagnosingNow, let's dive in to see how I solve the aforementioned problems in BRT.nvim.

Components

Now, building an atuin clone from pure scratch is going to be quite a task: self-implementing fuzzy finding, and writing a database from scratch and handling stdout/stderr ourselves will be quite hefty work. Instead, we'll be offloading some of that capabilities to fzf-lua, sqlite and tee.

Below shows a simplified diagram of how these things ties in together inside BRT.nvim

USER INPUT via <leader>b, or <leader>r or <leader>t

↓

Fetches all commands via sqlite database, which is clearable with :BRTClear

↓

Command Selection via fzf-lua, choices supplied by sqlite

↓

Command Execution via neovim's jobstart() + tee

↓ ↓

Viewable terminal log file available via :BRTLog

↓

Commands finishes running

↓

Store newly executed commands with relevant context back to sqlite

↓

Automatically populate quickfix list if exit code != 0Although the quickfix list is a component in BRT.nvim, I've decided to talk about it in the "Features" section as it makes more sense there.

fzf-lua

fzf-lua, in a few words, is basically fzf but in lua.

If you haven't heard of fzf, it is a searcher that updates your search result interactively as you type. For up to tens of thousands of commands to fuzzy find over, you can easily use telescope.nvim as well. For this project, I simply picked fzf-lua because I prefer the performance of fzf-lua over telescope for large repository.

Overall, the detailed docs and its ability to offload arguments to fzf itself means I can easily configure new keymaps as well as search behaviors.

For example, all this readable code resides in lua itself:

fzf_opts = {

-- Start with no selection

["--no-select-1"] = "",

["--nth"] = brt_util.pick_order,

["--delimiter"] = "|",

["--ghost"] = "...",

["--header"] = "EXIT CODE| TYPE|DURATION|COUNT|COMMAND",

["--wrap"] = "",

["--highlight-line"] = "",

["--ansi"] = "",

["--border-label"] = "HI",

["--border"] = "top"

},

input = true,To initiate a fzf search inside neovim with fzf-lua, one can call fzf_lua.exec_fzf(...) and pass in the list of commands;

imo, this is pretty straightforward.

With fuzzy-finding solved, the next big issue was persistence: how do we remember past commands? And who's supplying all the choices to fzf-lua? Enter sqlite.lua :)

sqlite lua

Hahhaa, I'm not sure if there's anything else to be said about sqlite. In lieu of implementing the data as a big table and risk some run time errors over some minor details, I let sqlite take care of the job of storing my commands.

For the schema, I store the command itself, the command type (build, run, or test), duration (how long it ran for), times inputted, timestamp for last inputted, as well as the exit code.

Regarding the portability of (aka the ability to remember) these commands when a user moves to a new machine (which is a thing that atuin offers),

I opted to create the sqlite database file as vim.fn.stdpath("config") .. "/brt_commands.db".

Basically, I assumed that everybody that uses neovim will also be using some sort of dotfiles, and when they move to a new machine,

they will often use some tools like stow or chezmoi, thus bringing the sqlite database file storing their

commands with them.

There is always the concern that logged commands could leak sensitive data, but since the project only focuses on commonly run commands such as ninja or npm or cmake and

I often only work on open source projects, I'm not quite sure if there is anything to be exploited hahahah.

tee

When we're launching a user-selected command, naturally, we would want to record the output for future inspection.

With such commands, we launch it via jobstart(), which gives us finer control over how stdout and stderr is handled. We can, of course, handle the output of stdout and stderr ourselves: combine them together and write to the log. However, doing so is quite laggy; when we're using tee instead, some commands are able to recognize that the output is not to the terminal directly (due to isatty()), thus reducing their printing and fall back to a more static progress report. By piping the output through tee itself, we'll be able to save a lot of processing power and storage this way.

A thing that I haven't thought about until I started adding tee to the executing command is that tee always returns 0,

rendering recording and reporting the exit code useless, that's why I add the following line to propagate the exit code

through tee itself: <your_default_shell> -o pipefail -c

Features

BRTLog

As mentioned in the section above, when the user runs a command, we would like to append 2>&1 | tee at the end of the command to allow us to store the output as well for future revisions.

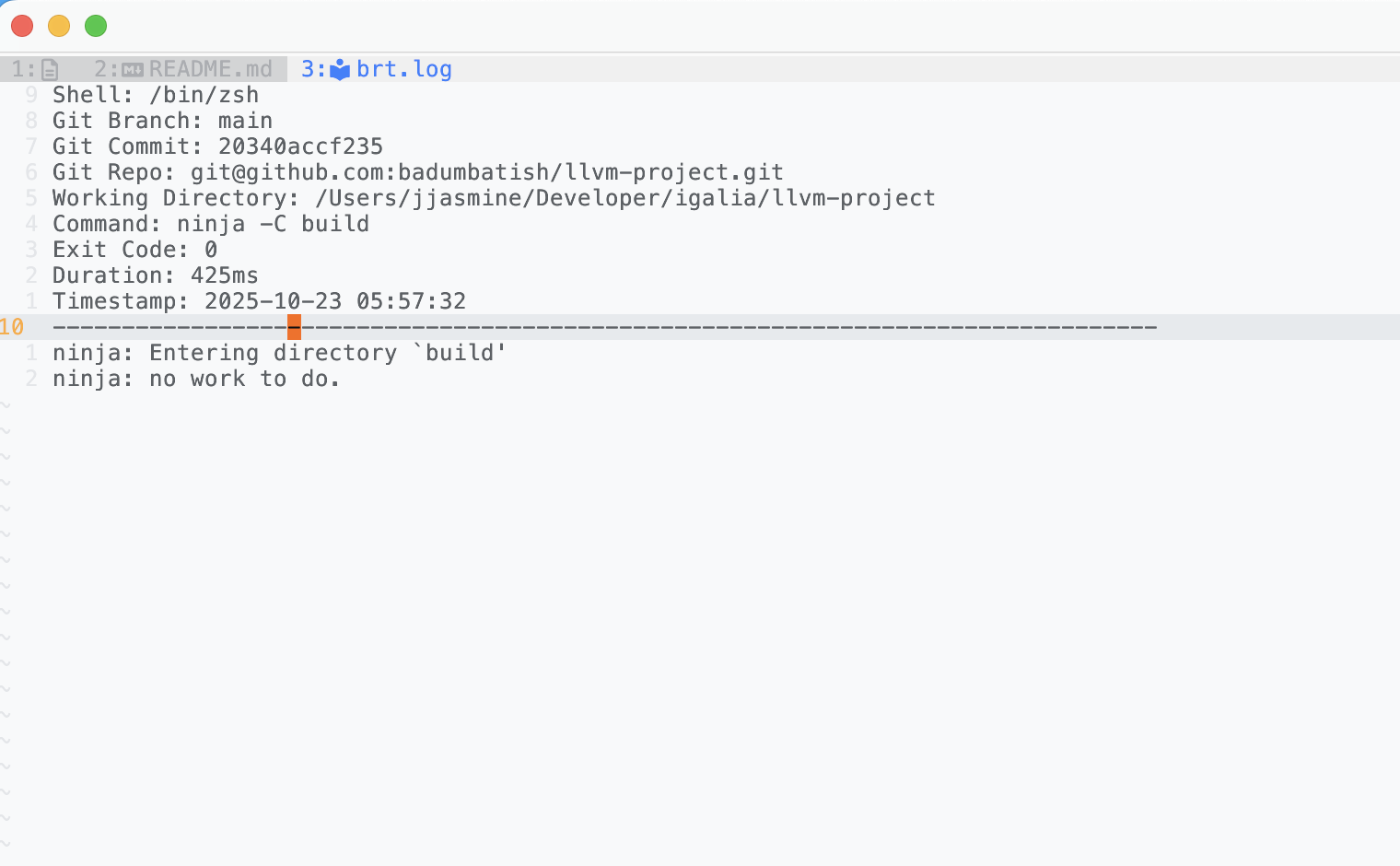

Besides logging the output of the command, BRT also logs the following:

- The system shell.

- Git commit, branch and repo: To help developers with which version of the project they're building.

- The command itself: So we can see which command outputs the log.

- Exit code: To check if the command has any errors

- Duration: To see how long the command runs for.

Below shows an example of a brtlog file, invoked via :BRTLog

Besides supporting revisiting a log, I added the logging feature so that users can easily copy and paste the log to either a team or a chatbot like ChatGPT or Claude.

I recommend you set up a command like <leader>ya for yank all so save yourself a few keystrokes if you're doing this a lot:

utils.yank_all_in_buffer = function ()

local cur = vim.api.nvim_win_get_cursor(0) -- Save current cursor position

vim.cmd('normal! ggVGy') -- Yank the whole file

vim.api.nvim_win_set_cursor(0, cur) -- Restore cursor position

print('Yanked whole file to system clipboard')

end

vim.keymap.set('n', '<leader>ya', utils.yank_all_in_buffer, { desc = 'Yank whole file and restore cursor position' })Quickfix file

The quickfix list in vim and nvim is a global list of file locations, usually errors, warnings, or search results—that you can jump through using commands like :cnext and :cprev.

For vim/nvim users, the usual development workflow would be :make, :copen and then :cnext and/or :cprev. Some pain points would be:

- how to quickly change which underlying command

:makewill be using - how to access the log itself.

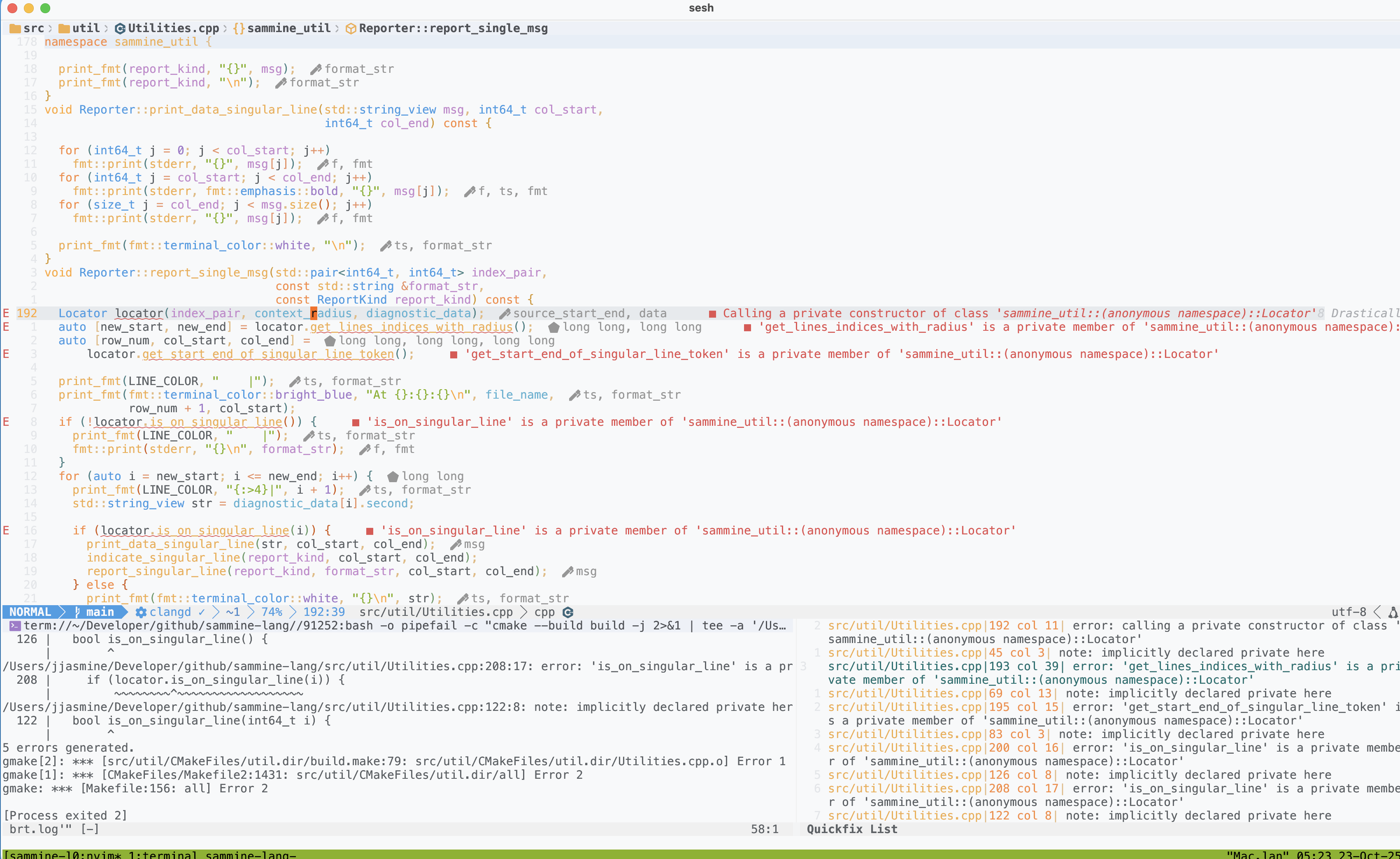

In BRT.nvim, for this, when a command fails, besides the already-spawn terminal buffer, I also populate and spawn the quickfix list with all the command errors. In this way, the quickfix list functionality acts as a personal reviewer for me, filtering out all the nonsense output and allowing me to focus my mental capacity on fixing build errors instead of locating the build errors and opening the files pertaining to them.

In my config, I map going to the next location in the quickfix list to n and previous location to m, so after quickfix list is populated, I can

just press n and m and neovim jumps straight to the error for me.

Here is a screenshot showing brt.nvim gathering all the error into the quickfix list for me, allowing me to be "lazy" and just press n and m to

go between errors.

Here is the lua command for mapping n and m:

vim.keymap.set("n", "n", "<cmd>cnext<CR>", {})

vim.keymap.set("n", "m", "<cmd>cprev<CR>", {})Sensible behaviors

One thing I learned writing BRT is that a good plugin isn't just about new features, it's about reducing mental page faults. Anything that saves context switches and mental capacity for users should be treated analogously to magic.

Sensible behaviors that achieve the magic goal is quite hard to program for. After all, how can you expect to write a plugin that acts just like your second skin: effortless and fun. Below lists a few sane and sensible behaviors that I've added to smoothen out the brt.nvim workflow :)

Keymaps

BRT comes with the same basic keymap that other neovim users might find familiar with:

<ctrl-yaccepts the current search result for you. Note that you'll still have to press<Enter>to run said command.ctrl-wdeletes a word in the search bar.ctrl-udeletes the whole search bar.ctrl-norctrl-j: go down the search list.ctrl-porctrl-k: go up the search list.

LSP to quickfix for current file

Sometimes you really don't want to compile the whole codebase to what went wrong, don't worry, I gotcha :)

BRT sets up two keybindings <space>le> and <space>lw to automatically pipes respectively the errors and the warnings

emitted by your LSP on your opened files directly to the quickfix list.

For <space>le, the quickfix list is populated with all opened files meanwhile <space>lw only populate the list with

the currently viewed file. The reasoning for this is because warnings are often isolated within a file itself, whereas

errors can be between different files.

Pre-populating commands

For new users, instead of having them type out some common commands such as cargo run or cargo build or cmake --build build -j4, BRT.nvim

populates these commands inside the sqlite database file by default so that users can just grab whatever they needed. A small but pretty

handy quality of life addition :)

Priming last command based on type

About the motto of the project, of course, we can't always accommodate the request that every command that the user want to execute in 3 keystrokes. What the description

really meant is that when the user has already typed in and ran the command to succession, we would like the re-invocation of said command to take only 3 keystrokes.

With <leader>b (in my config, this translates to <space>b) being 2 keystrokes already, we would want (most of the time) the last command that was run, being inserted into the search bar for users, so they can just press <Enter>.

Returning cursor

After spawning the terminal so that users can inspect the command output, I often notice that I would have to navigate the cursor from the terminal back to the text file that I'm editing, missing out a few keystrokes of efficiency. Thus, I've made it so that after we'd run a command, the cursor automatically returns to the last location of the text file.

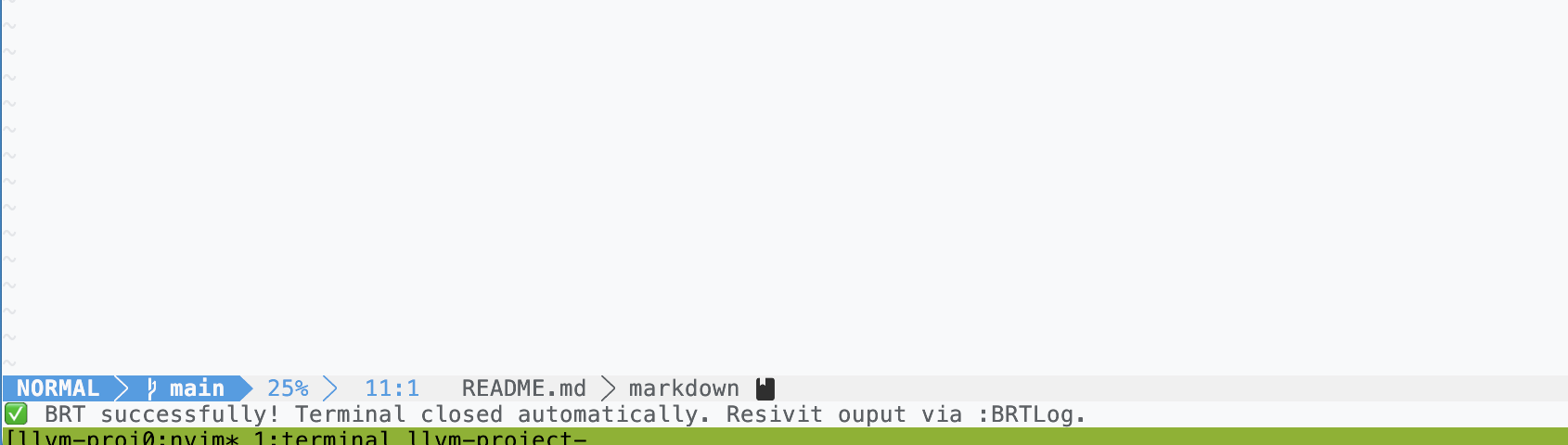

Auto-close on success

When a command is successful, I often noticed that I don't really care about its output anymore, I made it so that BRT.nvim automatically

closes the terminal buffer and displays a successful message; seeing only the green checkmark of ✅ saves me a few mental capacity

to type :q to close the terminal buffer as well as reading the terminal output to see if a command is successful or not.

Below is a screenshot showing what the message looks like

Auto-close on rerunning

If a user reinvokes BRT via <space>b, I found out that there is no reason to display the current terminal and/or the quickfix list anymore.

Instead of having to navigate to the two buffers and rerunning :q twice (that's a lotta keystrokes), I made it so that BRT automatically closes the two buffers,

allowing for some efficiency.

Hopefully after reading through this section, you'll realize that BRT.nvim have clearly separate itself from atuin :) The clickbaity title where I said I built an atuin clone is really just to drive traffic and to give you a sense of how the UI of BRT looks like - a bit like atuin.

Atuin-like UI

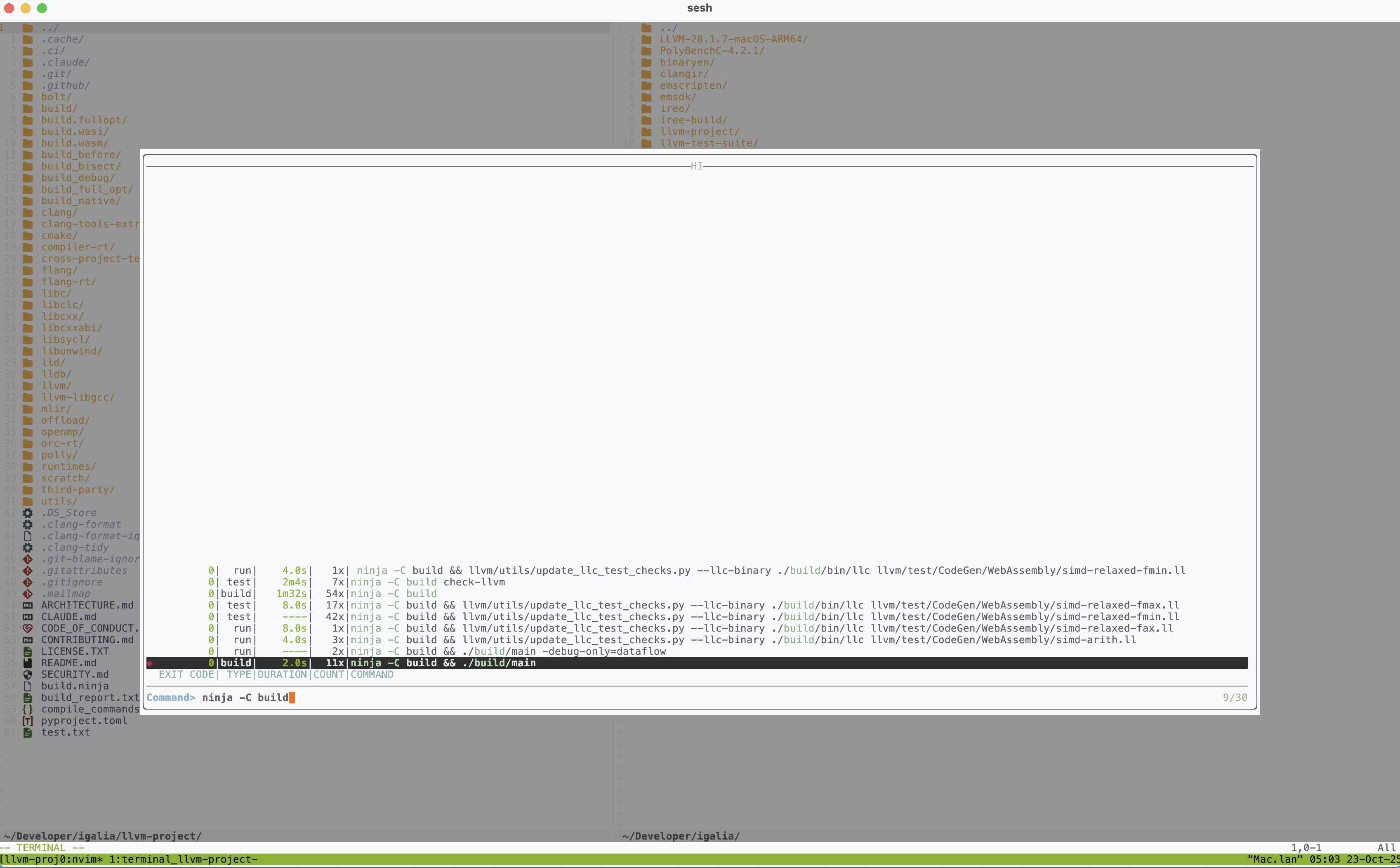

Just like atuin, with fzf-lua, we're able to offer fuzzy finding. On top of that, the UI is more focused on the development feedback loop itself. Since we don't care about how long since then we've run a command, BRT omits the "ago" feature and adds a column to display the exit code of the command; one thing interesting to note is that when a command ran successfully, the exit code and the command duration is displayed in green, and red when its exit code is non-zero. It also adds the command type as another column, either build, run or test.

The following screenshot shows a demo of brt.nvim opening when I press <space>b, priming my search box with the last command I ran

with "build" type, along with the necessary results. I also added a column to show how many times I've run certain commands,

just for funsies and bookkeeping.

For roughly 2 days, I've run all ninja -C build-related commands about 100 times or more. With how tight my development cycle has become,

I guess the plugin has already paid

dividends for itself :)

Ending

I hope you've enjoyed reading through how a clone tool of atuin came to be inside neovim itself :) I know I've really enjoyed writing the blog :)

BRT.nvim started on Aug 16 2024 as a simple neovim plugin that maps specific commands to certain types of projects

(cmake | cargo | npm | etc) without any UI/UX kind of improvements. A year and one month later,

after more clearly understanding my own pain points when programming, I feel like I've come a long way since then. BRT.nvim's new scheme

allows it to shine in areas where the old version would struggle: buggy in saving commands (no sqlite), not having a log file, no quickfix, no duration

or execution count, no fuzzy fnding, no

easy way to edit commands (user can only press <Enter> or they would have to go to neovim config to change the command).

I hope that after reading the article, you feel like BRT.nvim can help improve the workflow you have while programming inside neovim, or at least piqued by it. Please feel free to give it a try at https://github.com/badumbatish/brt.nvim.

I'll see you again soon :)